This month, the King County

Bar Association Bar Bulletin published Thomas

M. O’Toole’s excellent recommendations on how to prepare a deponent. Mr.

O’Toole is the President of Sound Jury Consulting, and his following advice is

well worth reading and heeding:

The deposition performance of a key witness is

critical to the outcome of any case. Summary judgment motions are often won or

lost on the testimony of central witnesses. Even when the case survives summary

judgment, unfortunate behavior or answers in depositions can have a detrimental

impact at trial, leading jurors to dislike or distrust the witness, which

lowers their motivation to want to find in favor of the party that witness represents.

I often receive calls from attorneys who are looking for

a witness preparation session just before trial for a difficult witness. The typical explanation is that the witness

performed poorly in his or her deposition and needs to improve for trial. These

calls are frustrating because, while I am happy to help, there is no need for a

witness to perform poorly in a deposition. There are a variety of strategies

attorneys can use to position a key witness for success in his or her

deposition. Unfortunately, these strategies are often not used and attorneys

instead rely on deposition preparation sessions with witnesses that create more

problems than they do solutions.

The purpose of this article is to discuss the right and

wrong ways to prepare a witness for a deposition. All key witnesses should go

through this process. Attorneys should avoid making an assumption that a

witness will perform well in a deposition because he or she is smart, sociable,

or a good communicator. The trenches of daily life vary greatly from the

trenches of a deposition. Skill sets that make a person successful in daily

life do not necessarily translate to or prepare a witness for a deposition.

There is no greater example of this than former President Bill Clinton. Clinton’s

defining trait was his communication skills. He was a smart, charismatic man

who was known for his ability to adapt to just about any situation and

demonstrate excellent communication skills in the process. When he was deposed

in the Paula Jones sexual harassment lawsuit, most expected a solid

performance. The American Spectator described Clinton as the kind of witness

“who would strike fear into the hearts of opposing lawyers.” However, his performance was anything but.

The American Spectator went on to describe him as “an unsophisticated witness,

revealing a desire to please the opposing lawyer, and telling prepared stories

that suggested he had lots to hide.”

In order to understand the right ways to prepare a

witness for a deposition, let’s start by looking at the wrong ways to prepare a

witness. The typical preparation session between a witness and an attorney

involves both of them sitting down in a conference room for a few hours or more

and talking through the case. The attorney probes the witness on issues the

attorney needs to know more about and gives the witness all sorts of advice on

how to talk about different issues in the case. The session usually ends with a

homework assignment for the witness requiring him or her to review a bunch of

documents and try to remember an unreasonable amount of items.

There are several reasons this approach fails. First, the

witness will not remember the majority of what he or she was told. All of the

studies on recollection suggest the witness will remember about 10-20% of what

he or she was told in that session. Second, the witness is not given the

opportunity to practice the testimony, which is critical. Witnesses need the

experience dealing with all of the standard attorney tricks. They learn this

through actual practice. Third, all of the tips and advice from the attorney can

be overwhelming. Depositions are intimidating enough and now the attorney has

piled on all sorts of “important” things the witness “must” remember. In short,

this cramming approach does not work and can often backfire. Witnesses perform

poorly when they feel overwhelmed and not in control.

The difference between an ineffective and an effective

prep session is what I would describe as an “attorney-centered” approach versus

a “witness-centered” approach. The former focuses on the attorney’s needs while

the latter focuses on the witness’s needs. The fundamental goal of any prep

session should be giving the witness comfort and confidence, which are

essential to a successful performance. Everything else derives from these two

items. I often joke that witness prep sessions are actually therapy sessions.

In this respect, the joke is half-true. Comfort and confidence empower a

witness to see clearly and take control of what his happening in the deposition.

Let’s now look at the practical strategies for giving a

witness comfort and confidence.

1. Determine

what the witness can realistically accomplish in his or her deposition. This can vary greatly among witnesses and will

impact the approach the attorney should take. For example, the goal for some

witnesses may be as simple as not “bombing.” In another instance, the witness

may be better suited to carry the weight of the case. An honest assessment is

critical here. I have seen attorneys try to get witnesses to take on more than

is realistic, which overwhelms them and ultimately leads to poor performances.

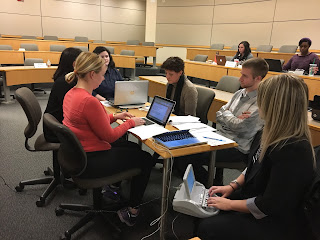

2. Practice the

deposition. The attorney should sit

across from the witness in a conference room and pretend to be opposing

counsel, asking all of the questions and deploying all of the standards tricks

one would expect from opposing counsel. The witness should pretend it is the

actual deposition. This gives the witness an opportunity to fail and learn from

it, which is much more impactful and memorable than merely discussing the case

for a few hours. Witnesses need to get used to the environment of a deposition

and the failure to practice forces them to learn and adjust during the actual

deposition. Conduct this practice in 10-15 minute segments and do not let the

witness call “time out” when he or she is uncertain about how to deal with a

question. The attorney needs to see how the witness will deal with it when he

or she cannot call “time out.” Each 10-15 minute segment should end with a

discussion of where the witness can improve as well as what he or she did well.

Positive reinforcement in the form of the latter is critical to maintaining the

witness’s comfort and confidence.

3. Identify a

few basic ground-rules and try to tie all of the feedback back to them. I usually start my prep sessions by explaining to the

witness that depositions can be very easy if the witness just follows a few

basic ground-rules. This helps ease stress and creates confidence in the

witness that he or she will be able to get through the deposition without any

major blunders. I usually provide four ground-rules. First, the fundamental

task is to listen to the question and answer only that question as efficiently

as possible, while correcting any problematic language or assumptions that need

to be corrected. It’s the most painfully simple (but effective) tip for any

deposition, yet witnesses get so overwhelmed that they lose sight of this

simple, important rule. As part of this, I explain that listening is actually

more important than talking in a deposition. Sometimes, I’ll ask witnesses to

adopt the habit of rephrasing the question in their answer, which helps ensure

they are listening and catching any problematic language or assumptions in the

question. Second, I tell them that all of their answers should come from one of

three places: what they personally know or remember, what the records show, or

what their common practice was. Anything beyond these three sources is

speculation and should be avoided at all costs. Third, I tell witnesses to not

be afraid of saying “I don’t know” or “I don’t remember” if it is the accurate

answer. Many witnesses treat depositions as a test where “I don’t know” or “I

don’t remember” is a wrong answer. This leads to speculation and inaccurate

answers. Finally, I tell them to own the facts, not run away from them. I will

usually highlight what I believe the bullet-point summary of the case is and

help them appreciate that there is nothing to run away from, which means a

“yes” answer should not become a “yes, but…” answer followed by a lengthy

explanation. These “yes, but…” answers sound defensive and suggests insecurity.

The simplified, bullet-point summary of the case also helps witnesses

understand and talk about the case in a more clear manner. In my experience,

the vast majority of problems get back to the witness violating one of these

four ground-rules. By keeping it short and simple and trying to tie feedback to

these points, the witness will start to realize that he or she does not need to

be intimidated or nervous and has the ability to take control of the deposition

and perform well.

4. Let the

witness complain or rant. If

something is bothering the witness about the case, the parties, or anything

else, let him or her rant about it. It can be painful to listen to sometimes,

but it is important for the attorney to understand what is going on for the

witness and it is even more important for the witness to have an outlet for

those concerns. If the attorney does not provide the outlet in the prep

session, the deposition becomes the outlet. This results in long, rambling

answers that become fodder for opposing counsel’s opening statement.

A whole book could be

written about preparing witnesses for their depositions. It is difficult to

limit the discussion to the length of an article for the Bar Bulletin since

there are so many tips and tactics for improving a witness’s performance in

deposition, but hopefully these tips provide attorneys with a good springboard

for an effective witness preparation session. The key is practice. It is this

experience and feedback that will best arm your witness for success in a

deposition.

Thomas M.

O’Toole, Ph.D., is president of Sound Jury Consulting, LLC, in Seattle. You can learn more about Sound Jury

Consulting at www.soundjuryconsulting.com.

Reprinted by permission of

the author Thomas M. O’Toole. Originally published in the February 2015

issue of the King County Bar Association Bar Bulletin. Reprinted with

permission of the King County Bar Association.